A Better Model for Valuing Startup Equity

If you’re joining a startup and want a good financial outcome, there are two critical things to get right. Ensure that there is some probability of an IPO and that your stock won’t expire before it happens. Unfortunately, most equity advice is bad and distracts people from these two important points.

The most insidious advice is “don’t join a startup for the money.” It discourages people from joining startups or encourages them to treat their equity like a lottery ticket. Startups might pay lower salaries, but they’re one of the best ways to create wealth. You just need to be diligent about choosing a good one.

Why is most advice about equity incorrect? One reason is that feedback loops are long and often single-threaded. If someone tells you that a company will never be big, it may take years to prove them wrong. Another is that valuing startups is counter-intuitive, and people’s first instincts tend to be incorrect.

Here’s an example — let’s say you have options to buy 0.01% of a company’s stock. It costs $100,000 to exercise, and the last round from two years ago valued your company at $15B. How much are your options worth? The most common answer — $1.4M minus taxes — is wrong.

When investors buy shares at $15B, they do it because they believe the company’s expected value is higher. Private valuations1 also don’t update between rounds, and the market or business fundamentals may have changed significantly. Finally, good deals for investors aren’t always good for employees. Investors write many checks, but an employee can only work at one company at a time. An investor might equally prefer a 1% chance of $10B or a 10% chance of $1B, but an employee should pick the latter 2.

A first principles approach to valuing equity

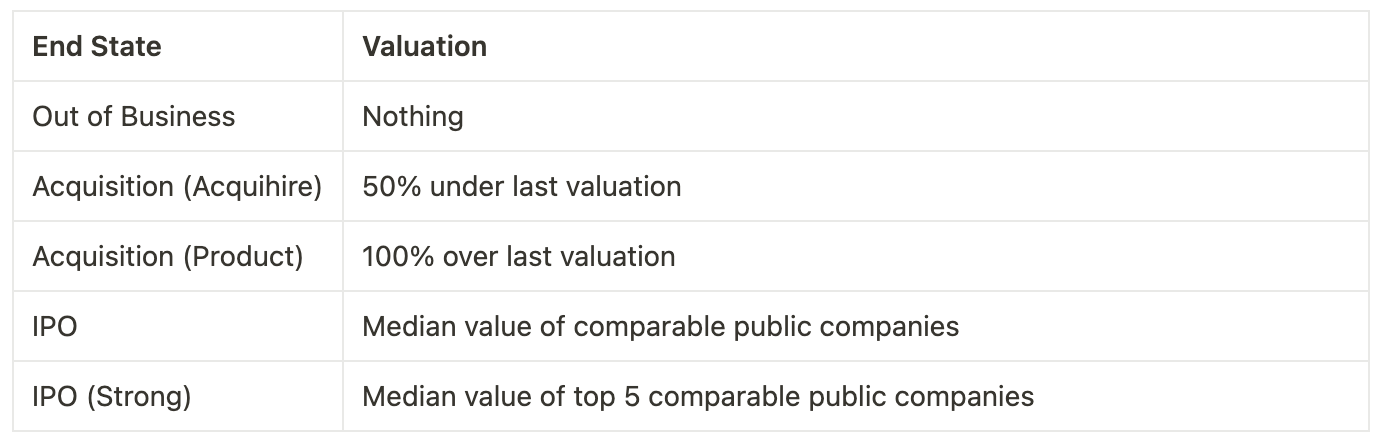

A better way to value equity is to construct an expected value (EV) model. Startups have a few common end states — going public, getting acquired for talent or product, or going out of business. The EV is the sum of the valuation x probability x ownership for each outcome. Build your model by outlining the scenarios with approximate valuations for each:

The acquisition outcomes in the table might seem pessimistic but remember that overhang clauses require investors to get paid out first. Only a tiny handful of product acquisitions meaningfully increase the value of the stock for employees.

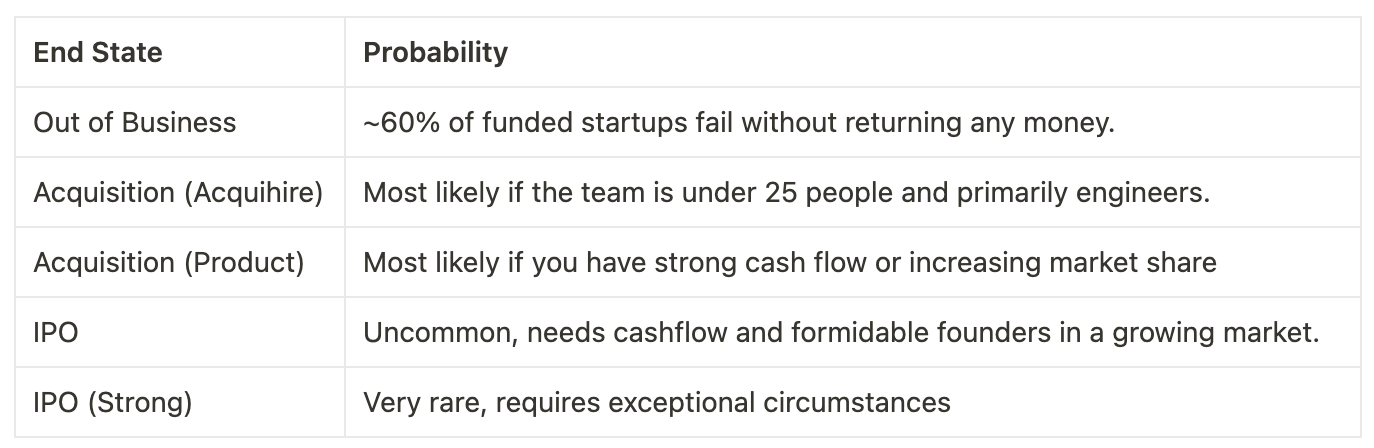

Probabilities are more nuanced and depend on the company. If you know angel investors or VCs in your market, you could ask them for advice. Asking the founders might also work if you have a direct line to them. All else failing, you can come up with your own estimates with these rough guidelines:

IPO probabilities are tricky to estimate, but you can look to historical data as a starting point. Approximately 2.5% of seed-stage startups reach a $1B valuation, and many of them will go on to IPO. If the company is later-stage, has very unusually strong fundamentals or exceptional founders, the odds will be even better.

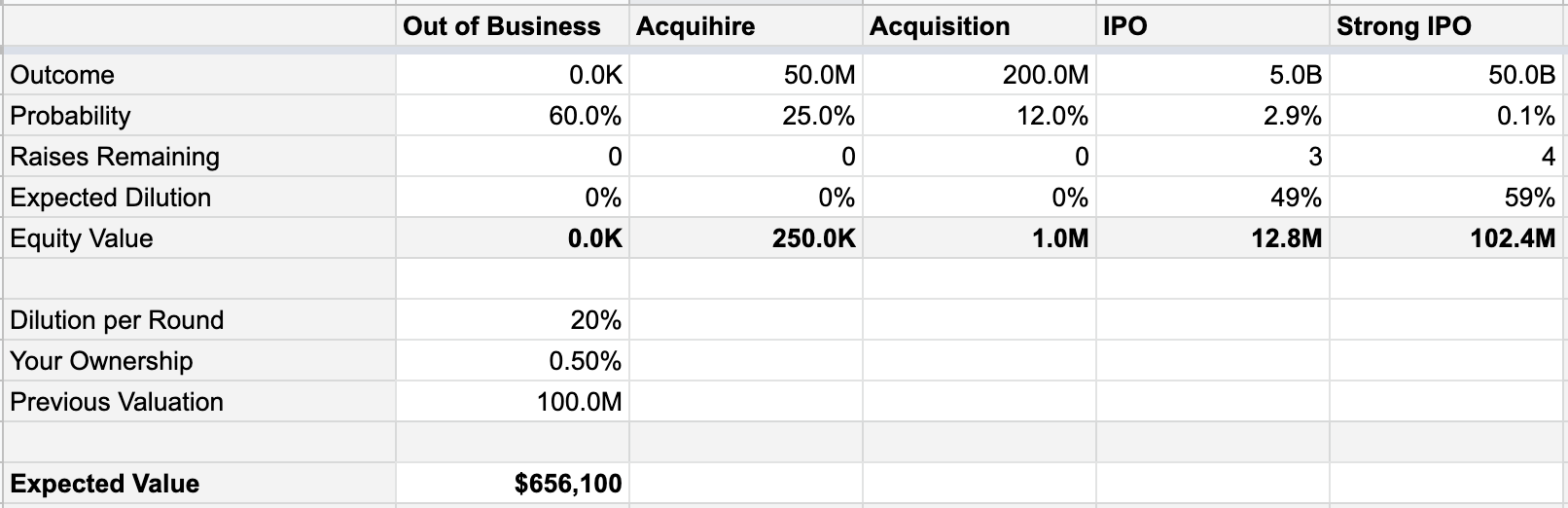

Plug these numbers into this spreadsheet to get the expected value. Don’t forget to account for dilution, which happens at every round. The typical range is 10-30% dilution per round, depending on the public markets and how well the company is doing.

What surprises people is how much the expected value depends on the outliers. Everyone knows this conceptually, but it isn’t intuitive. A slight increase of 0.1% in the strong IPO column adds $130,000, while the same increase in the acquisition column adds less than $1,000.

People with offers from different industries will also be surprised by how much IPO valuations change by market. The five largest biotech companies have a median valuation of $300B. The five largest consumer tech companies are closer to $1.5T. If you work at a biotech, you’ll need 5x the amount of equity or be 5x more likely to IPO to match your consumer tech peers3.

If you’ve been following along, it should be clear that the only thing that matters is picking a company in a good market with a reasonable chance of going public.

Don’t ignore the fine print

Startups are taking a long time to exit as private markets are more willing to fund them. The IPO timeline is close to 10 years and increasing steadily. This creates problems for employees whose equity might expire worthless before then.

The most common equity structures are restricted stock awards, stock options and restricted stock units (RSU’s). Both RSU’s and options come with an expiry clause, after which they are worth nothing. If you can’t early exercise, and you don’t believe that the company can IPO in that timeframe, you shouldn’t take the offer.

Stock options usually have a 90-day exercise window. If you leave the company, you must exercise them and pay taxes. The more successful the startup, the more expensive this becomes. Employees who leave early or get fired lose most of their vested stock options because they cannot afford the cost of exercise.

Employees undervalue exercise windows and expiries during negotiation, encouraging companies to keep them short. Some companies offer long windows because they believe it’s right that you share in the upside. These are the companies you should work for because they’ll treat you well when the hard times come.

How should you model this? Calculate the date you will be forced to exercise which is your estimated departure date plus the exercise window. Then estimate the probability that the IPO doesn’t happen before this date. Finally, multiply it by 80%4 and discount it from the value of your equity.

Comparing different offers

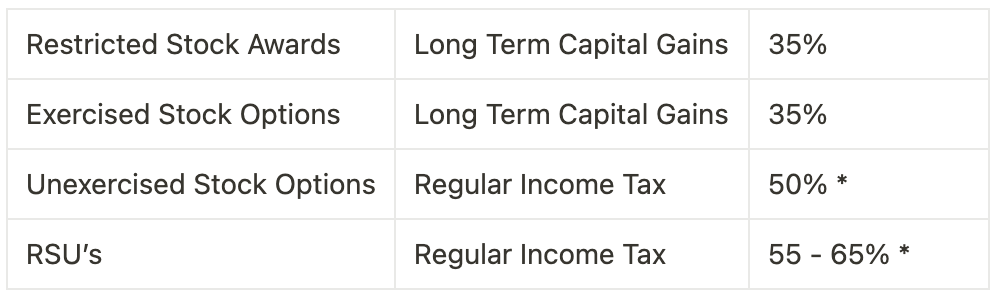

Tax treatment has a big impact on the income you get to keep. Some options are more efficient and can save as much as 20%. Make sure you account for them when comparing offers. The table below provides approximations 5 for tax rates which can be helpful in a pinch. It’s important to be clear that this isn’t financial advice; it’s a very rough heuristic. If you are going to take an offer at a startup, consider finding a good CPA.

Restricted stock awards are usually cheap to buy and incur long-term capital gains. Stock options are efficient if early exercised; otherwise they are taxed as regular income. Both restricted stock and options may also benefit from QSBS6. RSU’s are the least efficient because they are taxed before issuance. They may also have an AVG clause which means the number of shares vested reduces if the valuation increases.

Finally, this percentage is applied as a discount on the expected value to get the expected income:

Conclusion

Startups are a great way to build wealth if you’re willing to sweat the details and choose well. It’s important to choose one that you’re genuinely excited about. But if you find yourself having many to choose from, this framework can help you find the one that may have the best economic outcome.

Thanks to Dan Romero, Moh Almalkawi, Harj Taggar, Jesse Pollak, Charlie Harrington, Ryan Hoover and Nate Abbott for help with drafts.

This is not the 409A valuation, which updates often but does a bad job of capturing a startup’s potential. See Squaring venture capital valuations with reality ↩

See the Kelly criterion for a formal statement of this argument. ↩

As of may ‘22, the top 5 biotech are J&J, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Roche and AbbVie and the top 5 consumer tech are Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Tesla. ↩

The assumption is that you will only be able to exercise a small portion of your equity. ↩

Assuming that you were a California resident with $2.5M income, the effective long-term cap gains rate becomes 35% and the effective income rate is 50%. ↩

QSBS is a moving target but might save you several million in taxes. ↩