Sufficient Decentralization for Social Networks

Every year, centralized social networks place more restrictions on what users and developers can do. They seem to believe that limiting choices is the path to a healthy network, while the opposite is probably true. A decentralized social network can challenge this hypothesis by making two powerful promises that centralized networks cannot. They can guarantee that users own a direct relationship with their audience and that developers can always build apps on the network.

Centralized social networks closely control their users’ ability to reach their audience. They highlight some posts and suppress others to increase page views and ad revenue. But reliably reaching an audience is valuable to users and not just in a post-and-get-paid kind of way. For example, Elon Musk’s Twitter following makes it easy for his companies to raise billions from the public. When people discover that companies are restricting access for their own benefit, they are understandably frustrated. They’re even more upset when they realize that companies control their identity and can kick them off the network with no recourse.

Networks have also had a contentious relationship with developers, who brought in millions of early users. Developers built alternate clients, invented UI paradigms, and even launched billion-dollar gaming companies. But as they grew, the networks realized that they didn’t need developers anymore. Most users were locked in and wouldn’t leave because they’d lose part of their audience. Developer APIs became a liability that reduced revenue and increased complexity, and were limited or turned off completely. Now, only people who had political power within the company could experiment with new ideas.

A decentralized social networking protocol could change this dynamic by ensuring open access to the network. Companies can still make money by offering services, as Gmail does with email and Github does with Git. But decentralizing access ensures that they can’t be monopolistic and ignore users. It creates a market-based approach where the best ideas can compete on equal footing.

Sufficient decentralization

A social network achieves sufficient decentralization if two users can find each other and communicate, even if the rest of the network wants to prevent it. This implies that users can always reach their audience, which can only be true if developers can build many clients on the network. If only one client existed, it could stop users from communicating. Achieving this only requires three decentralized features: the ability to claim a unique username, post messages under that name, and read messages from any valid name.

Of course, social networks do more than send messages. For starters, they organize them into a threaded feed, send push notifications, and recommend new users to follow. These features aren’t easy to decentralize, and the list of things that people want will grow faster than the ability to decentralize them. But these features don’t compromise sufficient decentralization, so clients can build them in a centralized way. Email takes a similar approach, where sending messages is part of the protocol, but clients must develop their own spam filters.

Some believe that decentralization requires the entire social network to be on a blockchain. This is unnecessary and even undesirable. Social networks generate petabytes of data every year, which can be very expensive to store on-chain. Blockchains also make it difficult to delete data forever, which is a desirable feature for users. A network design that leverages on-chain systems to decentralize ownership while using off-chain systems for a better user experience is a better path to building social networks.

We’ve spilled a lot of ink over decentralizing social networks, but most users are still on centralized ones. Why hasn’t this changed already? There are three challenging problems with decentralizing social networks that have slowed adoption: scaling networks, decentralizing the name registry, and building novel social primitives. But for the first time, there are practical solutions for all three problems.

Scaling Networks

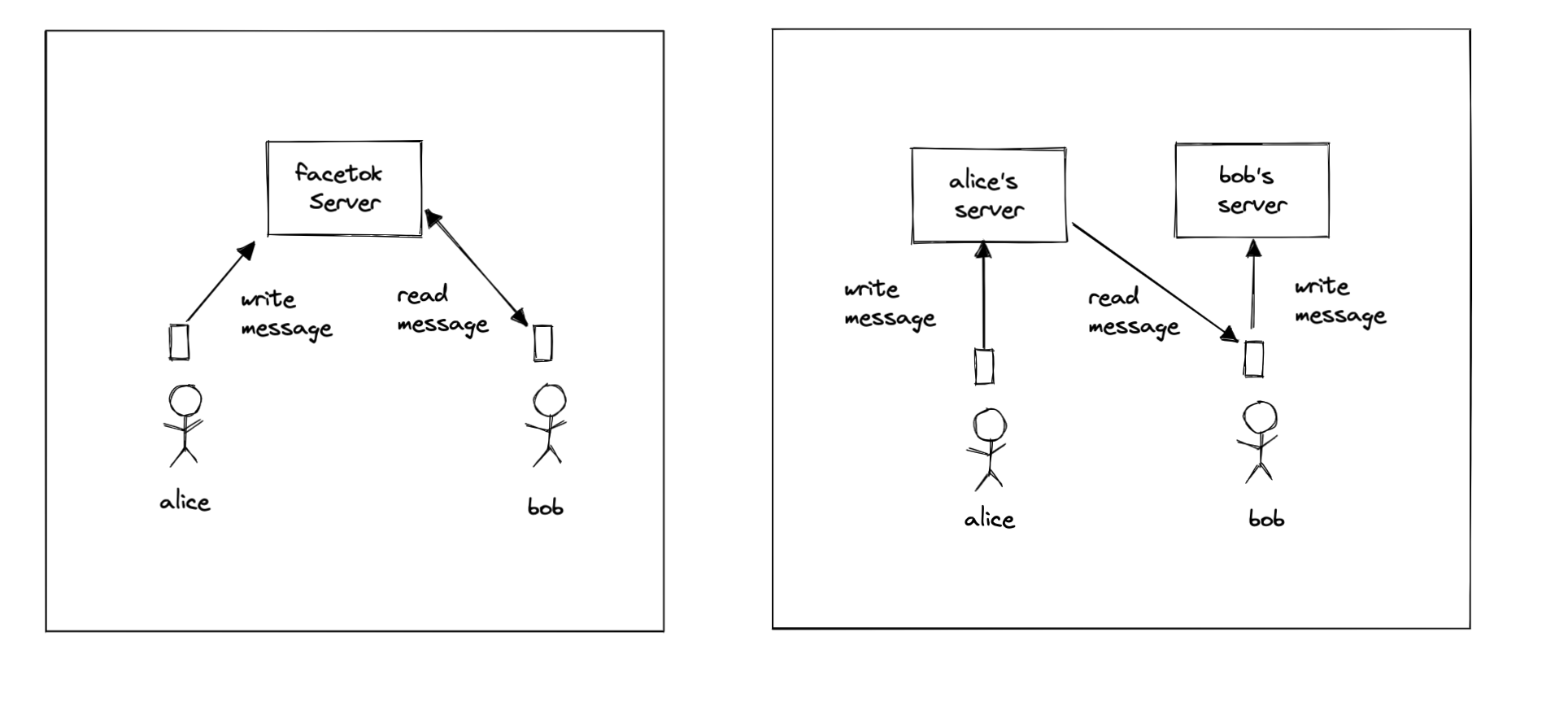

Social networks are a series of messages passed between users through a centralized server. An easy way to decrease centralization is to remove the need for a centralized server. Users could choose any server they like to store their messages and sign each one with a public/private key pair1. The public key becomes a unique identifier for the user, and the messages are tamper-proof.

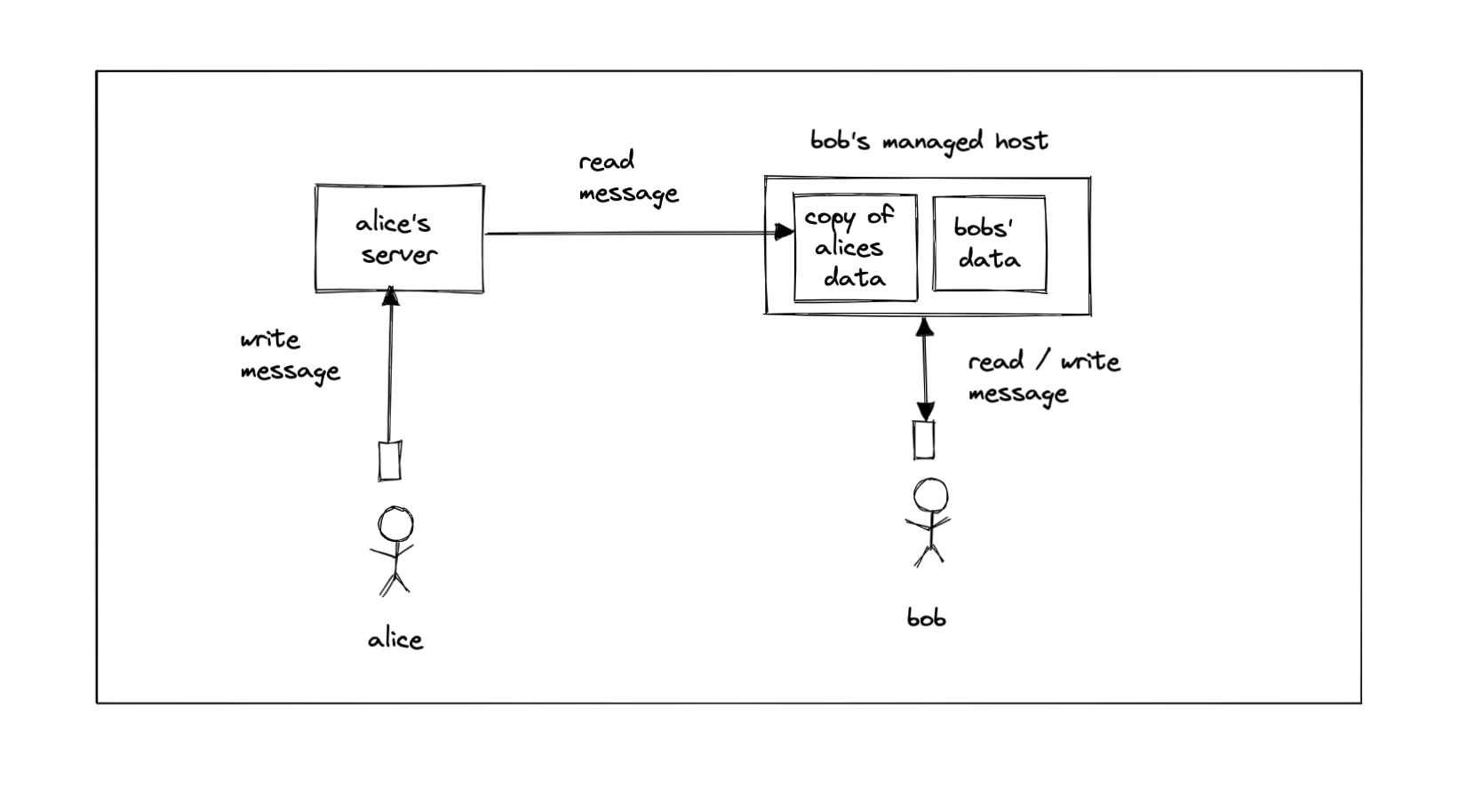

Using a social network in a decentralized way should be free and straightforward, but this is difficult in practice. Users want their messages available to all followers, which requires an always on-server in the cloud. A reasonable expectation is that self-hosting will be as complex and expensive as running your own website. But we can’t onboard billions of people by asking everyone to run a server.

This is where managed hosts come in. These companies host users’ social data, like Gmail and Outlook host email. Managed hosts can offer features that would be impractical for users to run at scale, like a content moderation system. They can provide better user experiences, and we should expect most people to use them instead of running their own server

A common argument against managed hosts is that they can centralize the network. For instance, popular providers could band together and charge users more for certain messages. Such actions are negative-sum over the long term because they incentivize developers to make new managed hosts and users switch to them. Protocols like email and cryptocurrencies made changing providers easy from day one, which in turn made collusion rare and short-lived.

Decentralizing The Name Registry

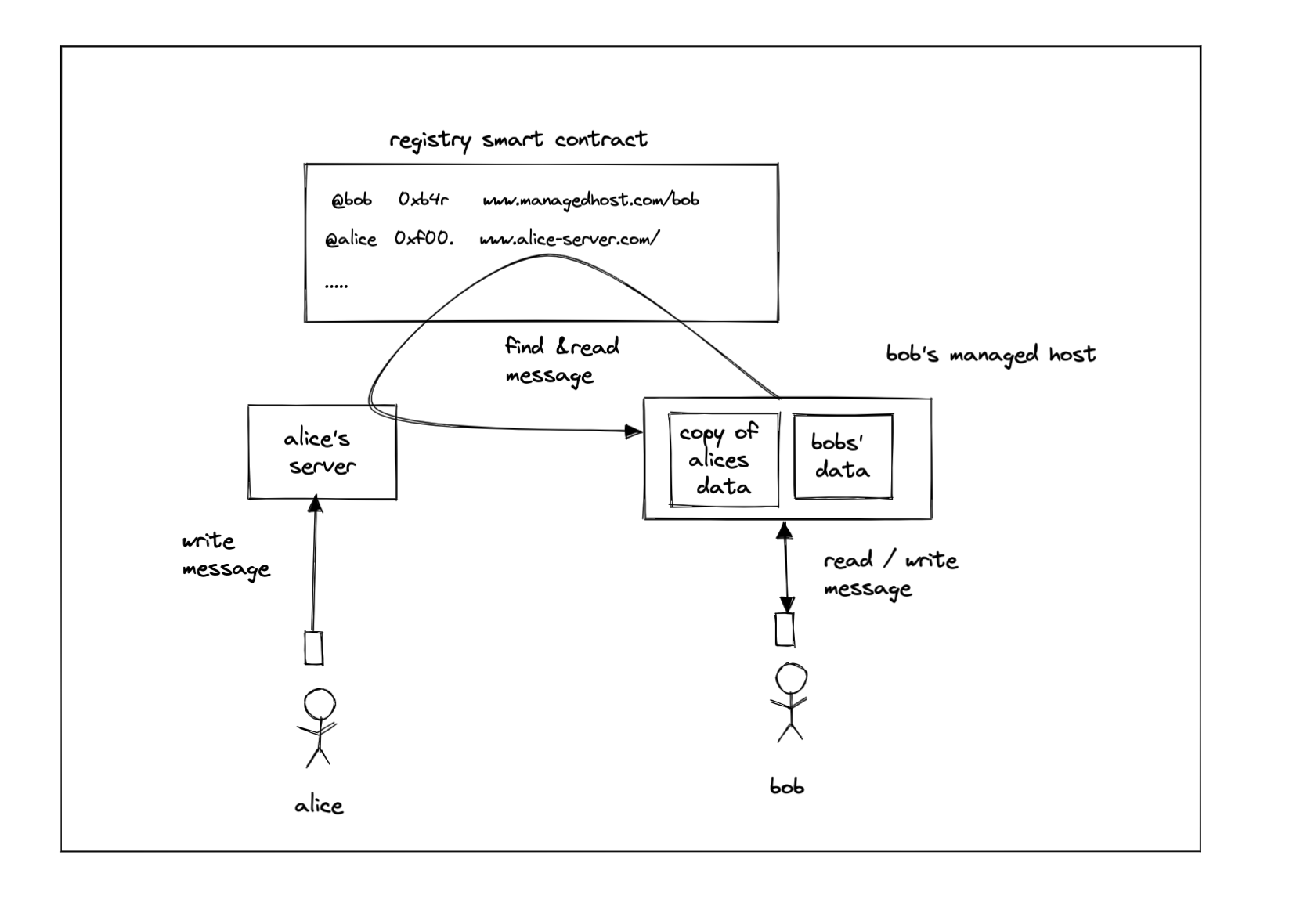

A user’s followers need to find the correct host to send and receive messages. A name registry can help map every user’s unique public key to a host URL and a memorable, unique username like @alice. A follower can ask the registry for @alice’s host and receive the correct URL. A decentralized registry that only allows Alice to change this URL protects them against malicious hosts. If a host stops serving their messages, they can modify the registry to point to a new host, and their followers will switch to the new location.

Decentralizing a name registry is difficult, and earlier attempts made difficult tradeoffs. ActivityPub doesn’t provide a way to use a managed host without compromising decentralization. Secure Scuttlebutt allows decentralization but doesn’t allow unique and memorable names, which makes identifying people harder. Keybase implements a registry but in a centralized way.

However, smart contracts have finally made decentralized registries possible. Users can make a transaction to a smart contract on a blockchain that performs the functions of a decentralized registry. The contract ensures that only that user can change the URL, and the blockchain provides conflict resolution if two people try to register the same name simultaneously. ENS and Unstoppable Domains have implemented similar systems on Ethereum.

The registry is the only part of the network that needs to be synchronized on a blockchain. All other actions can securely happen off-chain by signing them with the key pair. If you receive a message that claims to be from @alice, you can ask the registry for @alice’s public key and verify that the signature came from @alice’s private key.

Novel Social Primitives

Users don’t just want a decentralized version of an existing social network. What users really want from a new social network is status or entertainment, along with the benefits that decentralization offers. Any new network must offer a compelling way to achieve both, or it will face an uphill battle to get off the ground.

Blockchains have created novel ways to gain status. Being an early user, token holder, or voter confers status on people. Social networks for blockchain users can make it easy for people to generate proofs of such activity. The network could then offer features like token-gated communities, verified badges for NFT holders, and anonymous polls for token holders. The best on-chain systems are also highly composable, so a social feature designed for a standard like ERC-721 automatically works with every new token added to the network.

Successful social networks are usually built around a new communication primitive. Facebook had the wall, Twitter had the 140-character tweet and Snapchat had the ephemeral message. The idea maze of things you can do with decentralized identities, blockchains and zk-proofs is large, weird and interesting enough that there are probably many primitives waiting to be discovered. Decentralized social networks should explore this as a way to attract users. Offering a product experience that doesn’t yet exist is far more compelling than a clone of an existing network.

Conclusion

Centralized social networks influence every aspect of our lives, and their shortcomings are painfully clear. Improvements in cryptography and blockchains have provided workable solutions to achieve sufficient decentralization. We have a reasonable way to build a decentralized name registry, a hybrid off-chain/on-chain architecture to scale the network, and interesting new social primitives to build on. More importantly, people are unhappy with the status quo and want something better. If you’re an ambitious builder who wants to change the world, this is a great problem space to start working on.

Thanks to Dan Romero, Shaun Young, Tim Beiko, Lakshman Sankar and Brian Gu for help with drafts.

Inspired by Secure Scuttlebutt’s design. ↩