The Goldilocks consensus problem

Imagine that you wanted to build a sufficiently decentralized Twitter — a social network in which no single person or company is in control. How would you build something like that?

A social network is decentralized if it has many servers run by different people. The data would be spread across servers, so you’d need a simple way to answer questions like “What are the latest posts?”. This is where consensus comes in.

We developed a new consensus model for Farcaster, our decentralized social network. Existing models had user experience and decentralization tradeoffs, making scaling a social network difficult. Our model, called a deltagraph, uses blockchains and CRDTs to scale to millions, and hopefully billions, of users.

Why do we need a new consensus model?

Federation and blockchains, which are common models in untrusted networks, have tradeoffs that aren’t ideal for a social network. Federation is simple but leads to centralization, while blockchains prevent this but are slow and expensive.

In a federated system, anyone can run a server. Users pick the one they like, and all servers are loosely connected. In practice, federated services become oligopolies. Email is an example of this, where it’s very difficult to start a new server as a new developer. There are many unwritten rules and gatekeepers that you have to get past.

Without a forcing function, servers in a federated system diverge over time. APIs and data formats become slightly different, intentionally or due to bugs. Developers write workarounds that become implicitly enshrined, making the system more complex and opaque. Federated servers start out simple because there isn’t formal consensus, but this tradeoff creates systemic complexity.

Blockchains have a consensus model to prevent exactly this kind of problem. Unfortunately, the type of consensus they use makes them too slow and expensive for social networks. Twitter users generate over 100,000 updates a second 1, while a modern blockchain is 100x slower under ideal conditions 2. Users must pay for each post they add to the blockchain. It is hard to grow a social network under these constraints.

Would faster blockchains solve this? The tradeoffs that blockchains make to support financial transactions make this unlikely. Consensus must prevent double spending, which limits the strategies that can be used. People invent new ways to financialize things on blockchains which creates demand. The appetite for financial transactions seems insatiable even as supply increases, making it hard to store social data at a reasonable cost.

Social networks face a Goldilocks problem — federated consensus is too weak, and blockchain consensus is too strong.

Solving the Goldilocks problem with CRDTs

Blockchains reach consensus by letting one node decide the transaction order. Other nodes must send transactions to them and wait for a confirmation. This step is slow because it requires coordination over a network, but it is essential to prevent double-spending.

A social network network doesn’t need perfect ordering. Little harm is done if Alice’s posts show up in your feed before Bob’s. Farcaster’s consensus model - the deltagraph - uses CRDTs, which can reach consensus without coordination but do not guarantee a global order.

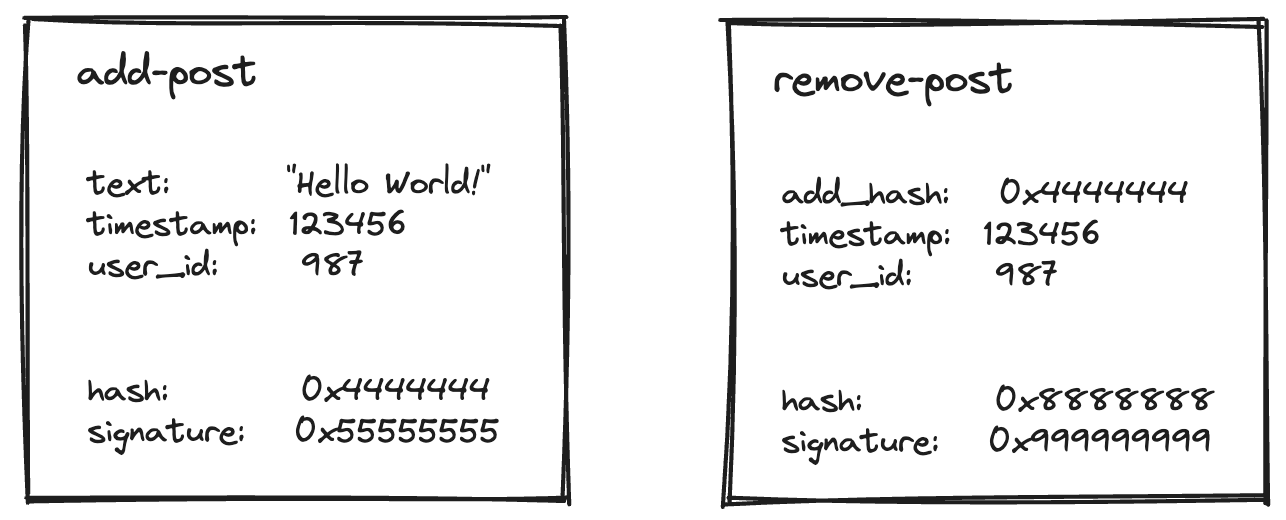

A deltagraph is made up of deltas, which are the atomic units of change. Deltas are stored on nodes, servers that accept them from users and forward them to other nodes. Alice can say “Hello World” by creating an add-post delta and sending it to a node. She can delete it later by sending a remove-post delta. When a node gets the remove, it will discard the add-post and store the remove-post instead.

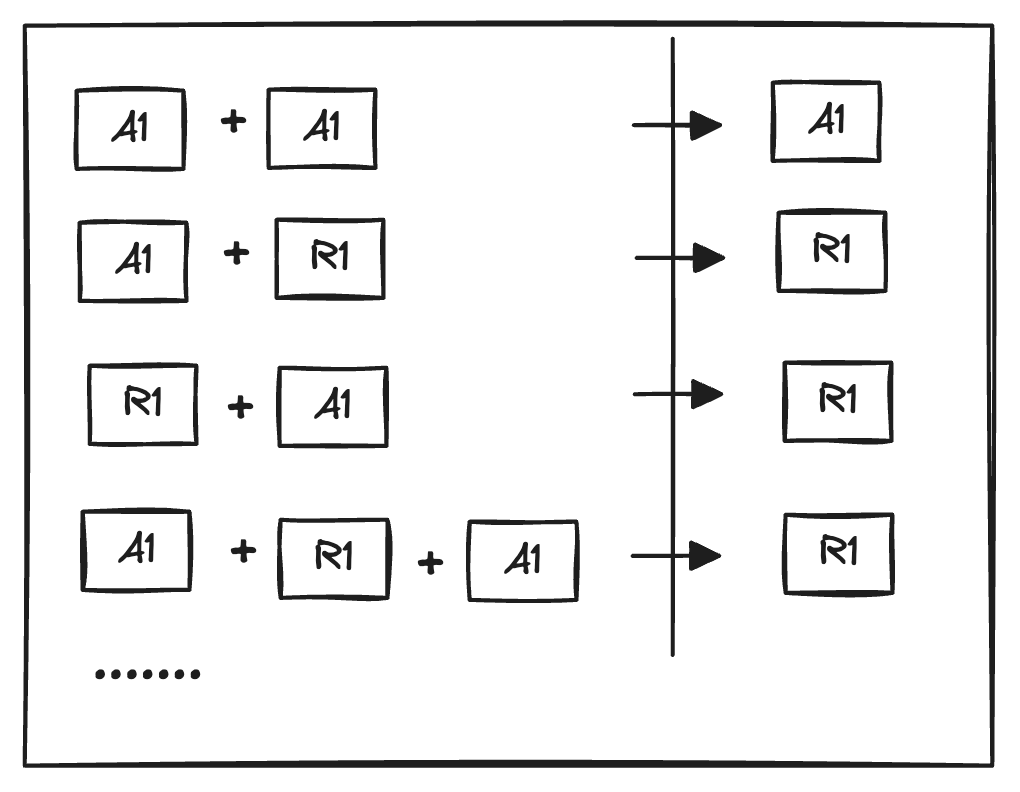

What happens if deltas arrive in a different order? A “remove-wins” rule handles this case. The rule says that if a post is removed, it can never be added again. With these rules enforced, you can send deltas as many times as you like and in any order, and they end up in the same state. This is very different from blockchains, where reordering transactions changes outcomes.

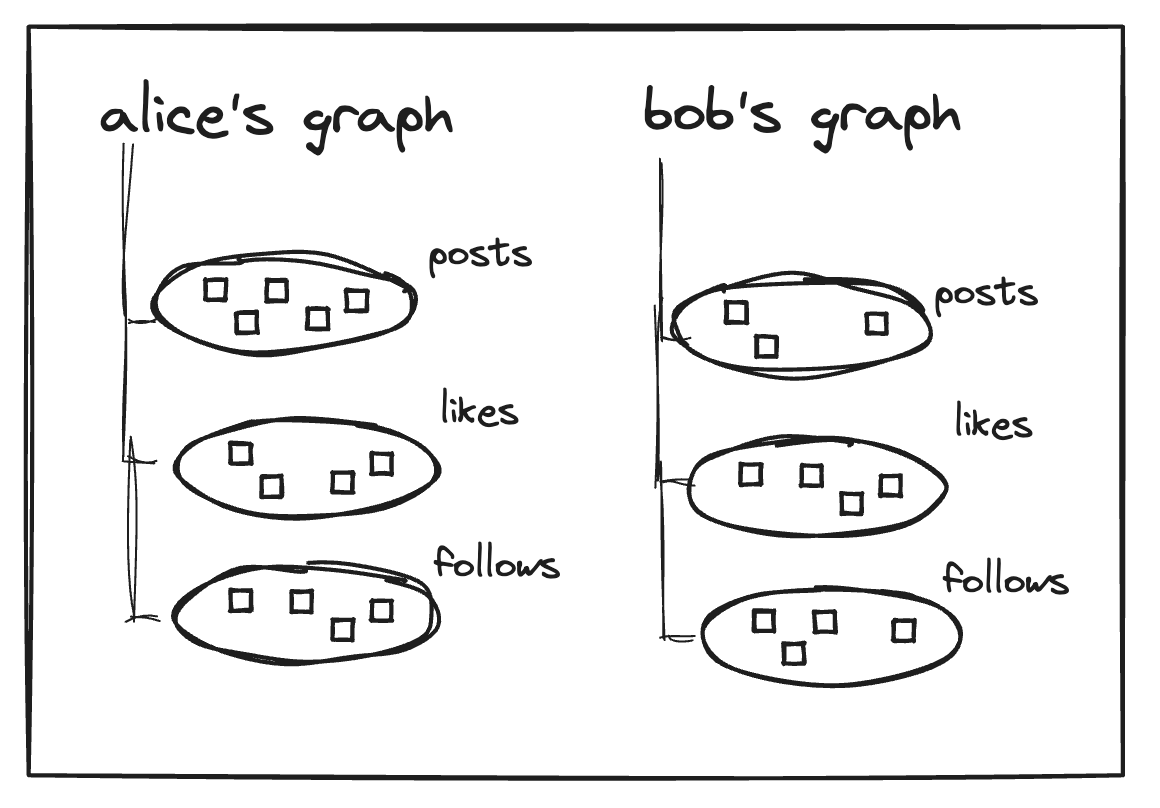

The deltagraph organizes deltas into sets and graphs. A set maps to something a user can do, like posting a message. It will store deltas related to that action and enforce rules. The rules are always commutative, associative, and idempotent, and they behave like anonymous delta-state CRDTs 3. A graph is a collection of sets that belong to a user.

Deltas across graphs can be merged without rules because they can’t affect each other. Even if Alice says “Hello world” and Bob replies, the deltas can be processed in any order. Deltagraph consensus is quick because it can run in parallel and without network calls.

Once a node achieves local consensus, it broadcasts deltas to other nodes. Syncing is more complex than blockchains because there is no global order. Two nodes have to compare all their sets to find missing deltas. There’s ongoing research to improve sync speed in deltagraphs.

Deltagraphs are much faster at consensus, but we still have a problem. What happens if someone broadcasts a billion deltas? Nodes would sync this with each other, run out of storage, and the entire network would crash.

Charging rent

Farcaster solves the overload problem by charging rent to store deltas. Users pay a storage fee and can post as many deltas as they like for a year. Nodes store a certain number of deltas for each user, and if the limit is crossed, the oldest deltas are removed.

In a feed-based social network, older messages expiring will have little impact on today’s feed, and users can rent more storage to keep a longer history around.

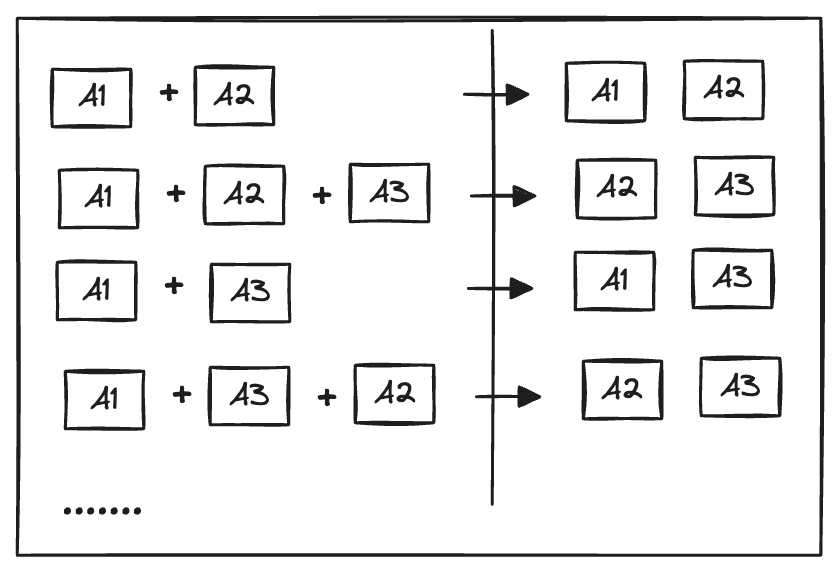

Deltagraphs apply a ‘last-write-wins’ which means that older deltas expire when the set is full. This rule can be stacked on top of the existing set rules while allowing deltas to be merged in any order. For instance, if Alice has three deltas with increasing timestamps - A1, A2, A3 - and the set can only store two deltas, the two most recent deltas will remain after the set logic runs.

The problem with charging rent is that the deltagraph can’t move money. This is a good thing because it reduces demand for space. We don’t want Alice, who is trying to post a photo of her cat, to compete with Bob, who is trying to day trade. But how do we collect rent?

Farcaster’s deltagraph relies on a blockchain to handle the ordered transactions 4. A user must first make an onchain transaction to create an account and pay rent from their wallet. They can then create a delta, sign it with their wallet, and send it to the deltagraph. The deltagraph tracks onchain events and verifies the delta’s signature before accepting it.

The deltagraph doesn’t have to worry about byzantine fault problems. Thanks to CRDTs, most actions don’t need coordinated consensus, and the few that do are outsourced to a blockchain. It’s only concern is handling p2p layer challenges like denial-of-service and eclipse attacks5.

What’s next for deltagraphs?

The deltagraph isn’t theoretical — Farcaster has been using it for a year and has over 300,000 paying users. The network has 1,000 nodes serving 5 million deltas every day. Our goal is to reach Twitter scale while staying decentralized and providing a great user experience, and we see a clear path ahead.

Deltagraphs augment blockchains, enabling applications that weren’t cost-effective before. This design pattern might unlock other use cases that we haven’t yet considered. Alternate approaches to consensus — CRDTs, verifiable compute, or something else entirely — could be paired with blockchains to decentralize games, marketplaces, and other consumer apps.

Thanks to Shilpa Lokareddy, Dan Romero, Georgios Konstantopoulos, Sanjay Raveendran, Cassie Heart and Polynya for help with drafts.

Twitter data is hard to come by these days. The last known number was 6,000 tweets per second. After adding reactions, follows and accounting for growth, the number is likely ~100,000. ↩

Decentralized blockchains range from 60 (Ethereum) to 1600 (Solana) today. Source. ↩

van der Linde, A., Leitão, J., & Preguiça, N. (2016). Δ-CRDTs: Making δ-CRDTs delta-based. ↩

Farcaster’s contracts live on OP Mainnet, but any programmable blockchain would work. ↩

Heilman, E., Kendler, A., Zohar, A., & Goldberg, S. (2015). Eclipse attacks on bitcoin’s peer-to-peer network. ↩